FRENCH RESTAURANTS IN CHICAGO:

1924-1999 A 75 YEAR RETROSPECTIVE

PART 1 : 1924-1959 A few glorious years and then a big gastronomic desert

Prologue: Me and Jacques French Restaurant in 1968

When I came to Chicago for the first time in August of 1968 to visit my wife’s relatives, everything was hot, hot, hot here: The weather, with temperatures shooting up to the mid 90s’, and the political atmosphere that was dominated by the very tense Democratic Convention and the riots in the streets.

From what I could observe during the 3 weeks I spent in Racine , Wisconsin , and Evanston , IL

Of course not speaking English at that time, having no car at my disposal, and staying at my sister in law’s house in Evanston during the week I spent here, I did not have any opportunity to visit Chicago

But I was told that Chicago

I sort of puzzled my in laws when I explained after a few days that we were used to drinking wine with our meal. So my mother-in-law took me to the local pharmacy in Racine to explain my problem to her buddy the pharmacist who had 6 remedies to suggest: Paul Masson’s Burgundy

I first tried to adjust to the softness and fruitiness of the so called Burgundy

When I arrived to Evanston

At the time I ignored the existence of Schaefer’s in Skokie, though it was very close to where I was staying, which actually was a very good wine shop that I discovered only 3 years later.

Anyway, back to 1968. One day, after the convention was over and the streets were returning to a more peaceful status, I took the El to go to downtown Chicago Michigan Avenue

We went to Jacques French Restaurant, a popular eatery that was at the time located at street level in the marvelous old-fashioned building at 900 N. Michigan Avenue

We were seated in a very charming room that was separated from the inner garden by high French windows. I was impressed by the environment and the apparent elegance of the décor and the customers.

Things started to go bad when the headwaiter who was speaking with a phony French accent came to take our order. My brother in law insisted on telling him that I was a Frenchman from Paris

Oui, Oui, Très Bien… that was all that the poor man could mutter.

I had an hyper-refrigerated avocado with shrimps topped by a pink, sweet sort of vinaigrette sauce, a ham omelette that was overcooked and almost compact, with soggy fries, and I believe a very sweet, gooey lime sherbet for dessert.

The worst part was when the waiter asked what kind of dressing I wanted on my salad, made of course of shredded iceberg lettuce with some filament of carrots and slivers of tired red radish. He suggested the “French” dressing of course. I could not swallow that sweet and creamy stuff that was anything but French.

I had a glass of a very jammy California Cabernet-Sauvignon. It was so bad that I switched to a Michelob beer.

I asked for an espresso, but the waiter told us that the machine was not working. I think that there was, in fact, no real espresso machine.

That was my first “French” restaurant experience in Chicago

I became suddenly very aware that I needed rapidly a fix of real French cuisine and started to count mentally the days that separated me from my return to Paris

What I did not know at that time, and that I discovered while doing a lot of research for this piece on French restaurants in Chicago , was that in fact there were some French restaurants in Chicago

For the time being, let’s just mention a few of these authentic French places that obviously none of my local contacts had ever visited at the time I was there: La Chaumière, Les Champs-Elysées, La Brasserie de Strasbourg, and of course Maxim’s de Paris and Jovan.

I will not mention all the so-called French restaurants of the Ray Castro and Edison Dick mini empire, of which Jacques was one of the flag bearers, that existed in 1968. We will say a few words about them later on.

The interesting itinerary of Jacques Fumagally: From the Ritz in Paris to Chicago

Let's go back for a minute to the origins of that phony French restaurant, Jacques French Restaurant which was actually started by a French man named Jacques Fumagally. I suspect that when he arrived in the U.S.

To be more exact, Jacques Fumagally was born in 1879 in Monte-Carlo, in the Principalty of Monaco Monte Carlo

Early in his career Jacques Fumagally did stints in prestigious establishments like the Ritz on Place Vendôme in Paris , and the Sevilla Biltmore in Havana , Cuba

John Drury, in his marvelous book Dining In Chicago, (published by John Day Books in 1931) tells us that in the late 20’s Fumagally was the very stylish Maitre d’Hôtel at the 180 EAST DELAWARE, a very classy restaurant just half a block east off Michigan Avenue, across from what is today the John Hancock Center.

The chef at that time was also French, one Julliard Medou according to John Drury. A complete table d’hôte dinner would cost around $1.50. Jacques Fumagally morphed that restaurant into Jacques French Restaurant in 1928 and it would remain at that location on Delaware until 1935.

The new occupant of the space at 180 East Delaware was a new French restaurant, Chez Emile. The restaurant would keep that name until 1945 when a Chicagoan born in Greece, Paul Contos, leased that same place and started another French-Continental restaurant called Chez Paul.

Chez Paul would stay there until 1965 when it moved to 660 N. Rush in the old Mc Cormick mansion.

At that time Jacques Fumagally decided to lease the space occupied by the ‘’900 restaurant’’ at 900 N. Michigan.

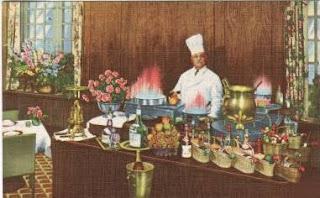

He invested lots of money in that new place, including creating the soon to be famous summer terrace in the inner open yard of the building, 3 dining rooms, a cocktail lounge with a very modernistic bar. Everything was air-conditioned. The new Jacques French Restaurant opened on June 1, 1935.

He invested lots of money in that new place, including creating the soon to be famous summer terrace in the inner open yard of the building, 3 dining rooms, a cocktail lounge with a very modernistic bar. Everything was air-conditioned. The new Jacques French Restaurant opened on June 1, 1935.

Problem is, I could not find any information on what kind of French cuisine they served in the thirties at Jacques French Restaurant. I do not even know who was the chef then. But I’m pretty sure that it was at the time a real French restaurant. In fact in 1939 they served bouillabaisse at the restaurant.

What is interesting is that the restaurant on Delaware

Jacques French Restaurant was acquired by Ray Castro, a Cuban immigrant that had arrived in Chicago in 1930 and worked as a bus boy, then waiter, and eventually captain at the celebrated Pump Room in the Ambassador East Hotel, with his partner Edison Dick, the heir to the copying machines company, in 1953. It is probably at that time that the restaurant lost its original French identity and became more ‘’continental’’ in style and cuisine.

Jacques Fumagally retired in Florida Chicago

Very few French restaurants in Chicago

I had wrongly assumed for a long time that the first real French restaurants in Chicago

I had done some brief research trying to find out if at the time of the World Columbian Exposition of 1893, some French restaurants might have opened in the city since France was part of the “food scene “ at the expo. But I could not find any.

In fact even though there was a big French Pavilion at the fair, and several French-inspired exhibits, pieces of architecture, and even streets modeled after the exotic venues at the Paris Fair a few years earlier, I could not find a single French eatery there.

The French chocolate company Menier had a big booth, there was a cider press in the French pavilion, and a French chef in…. the German pavilion, but that was about it.

In fact, I could hardly find any substantial evidence of a strong French presence on the Chicago restaurant scene before and after the Great Chicago

I found a mention of a French restaurant called Doussang, that seems to have been very successful around 1807. Located at 35 W. Adams St.

Much later, in 1882, there was another French restaurant at 77 N. Clark St.

And of course the famous DeJonghe restaurant, located on Monroe Street

The owner of the restaurant Barbara DeJonghe, a Belgian woman who arrived from Europe in 1891 and started the restaurant just before the World Columbian Exposition had a hard time at first selling her snails, imported live from Burgundy

But according to an article published in the Chicago Daily Tribune in November 1901, the World Columbian Exposition, and the exposure to all kind of different food products from different counries that it generated, modified the eating habits of many Chicago diners who developped a strong taste for snails.

DeJonghe restaurant started to sell a lot of French ‘’escargots’’ in exponential numbers: from 1,000 snails in 1896, to 24,000 in 1898, 500,000 in 1900. In 1901 they were expecting to import, serve, and resell to other restaurants in N.Y and San Francisco, 5 million of them.

According to this Trib article, in the early years of the 1900's it took 10 hours to process, cook, and put the escargots back in their shells for serving.

A similar new craving for clams and oysters had occurred in the late 1800’s.

Similarly, a Loop restaurateur told the Tribune that when he tried in 1891 to offer a free pint of French Claret wine with its $ 1.00 dinner, customers did not want the wine.

10 years later the Tribune said, 9 out of 10 guests dining in fancy restaurants in the Loop were ordering wine with their meal.

But there must have been some French chefs working in Chicago Athenaeum Building

The experience of Le Restaurant du Pavillon de France at the New York World Fair of 1939 that stimulated the creation of French restaurants in New York in the early 40’s and 50’s.

My reason for thinking that the World Columbian Exposition and its French influence might have had a stimulating effect on the creation of French restaurants in Chicago was that such a phenomenon happened in New York

At this huge event, the French Restaurant Owners Association had put together an incredibly popular beautiful 350 seats restaurant called Le Restaurant Du Pavillon de France. Its “brigade” of 24 chefs and cooks introduced a very large variety of dishes representing all aspects of traditional French cuisine to their American guests who never in their lives ever had an opportunity to taste so beautifully executed and served food in such spectacular settings.

At the end of 1939, the war was already raging in Europe . Henri Soulé, the Maitre D’ and some of his staff members returned to France, but then decided to return to New York to work at the Restaurant du Pavillon for the new season 39-40. With the aggravation of the situation worldwide and France

According to the marvelous book ‘’Dining In Chicago’’ written by John Drury, and published by John Day in New York City 1931,several very interesting French restaurants operated in this town between 1925 and the end of the Prohibition in 1933.

Drury was a journalist who after starting his career in N.Y.C joined the Chicago Daily News in 1927.His book is easy to find and to download on the web.

Speaking of Prohibition, John Drury who besides being a writer, poet, painter, was also a pipe-smoking bon vivant who once took a trip to Canada just to have a few drinks, describes early in the book the various French wines you should pair with French food. He amusingly recalls that in spite of the application of the 18th amendment, you can find wine in the city’s establishments, but of course he refuses to tell the readers which ones have the best wine lists.

It is interesting that, according to John Mariani’s America Eats Out, ‘’ De Luxe dining rooms fared poorly in Chicago under Prohibition and the owner of the defunct Richelieu restaurant once cried: I lost a million dollars trying to make Chicago eat with a fork’’.

It is true that you had to wait until 1938, when famous Chicago restaurateur Ernest Byfield opened the Pump Room in the Ambassador East Hotel, to find a restaurant in Chicago

In fact the evolution of the restaurant industry in the United States White Castle

Americans needed to feed themselves and their families as cheaply and conveniently as possible. The idea of dining out was more focused on hamburger and soda than on fancy French food, especially in small towns and rural areas. Obviously in large cities like New York , L.A and Chicago

Besides there were also some strong reactions in the restaurant and hospitality industry in the U.S.

So it was quite a surprise to me, when I read Drury’s book, to discover the existence of the following French restaurants in Chicago

The locations of these French restaurants were not necessarily concentrated in the Loop, especially around the Randolph Street Rialto Rush Street N. Michigan Avenue

All the following notes are directly inspired by Drury’s book.

JULIEN’S . 1009 Rush Street

Nowadays it could almost be called a family-owned bistro and would certainly have been my favorite. Started after WW I by Mr. Alex Julien, a former chef at various major hotels in town, this restaurant was the oldest French establishment in Chicago Chicago

CHEZ LOUIS 120 East Pearson

The owner, Louis Stefifen, a French-speaking gentleman from Switzerland Michigan Avenue Paris

180 EAST DELAWARE 180 East Delaware Place

For Drury, it was the “most charming and interesting French restaurant in Chicago

For the time it’s decor was quite fancy: beamed ceiling, tiled floors, draperies, fireplace, candles on tables, And of course, as mentioned earlier, the sophistication and charm of the host, Maitre d’hôtel Jacques Fumagally, whose experience at the Ritz in Paris

BON VIVANT 4167 Lake Park Avenue Hyde Park

Opened in the early 1920’s, this modest red brick house had become a bastion of French seafood cuisine that attracted the wealthy locals who lived in mansions, luxury apartment buildings and hotels in the University of Chicago, Hyde Park and Woodland area.

Two specialties were very popular: The fresh “homards” (lobsters) that came twice a week from Boston and Maine Paris

Table d’Hôte dinner was $ 1.50 and a lobster dinner only 25 cents more.

L’AIGLON 22 East Ontario

Filet Mignon Béarnaise, Moules Marinières, Escargots à la Bourguignonne, Poulet Meunière, Cuisses de Grenouilles (frog Legs) , Côtes d’Agneau Maison d’Or (lamb chops), Pâté de Foie Gras, Sole Marguery (in a sauce created at the famous Petit Marguery restaurant in Paris) those were only a few of the traditional dishes that you could find described in French on the menu.

By the way they had their fresh sole shipped from France

The French waiters would politely explain these specialties and even put together a sample French menu for you.

The atmosphere was very Parisian. And its wine list was probably one of the most extensive you could find east of New York City and included some rare Bordeaux

Since the owner and General Manager Teddy Majerus, a native from Luxembourg , had been working at La Louisiane restaurant in New Orleans

But he also had an extensive professional experience in French cuisine having worked as a caterer in some of the best places in Paris and London

The restaurant, that was located in an old mansion that resulted from the junction of 2 old brownstone houses belonging to a millionaire, had a client base made up of essentially wealthy and well-dressed business people from the Loop and celebrities from the Gold Coast, New York or L.A. All the rooms of the former mansion had been transformed into dining rooms, public and private, ballrooms and banquet halls.

I believe that prices were among the highest in town.

Opened By Teddy Majerus and his brother Alphonse in 1926, it was sold by Teddy in July of 1962.

MAILLARD’S 301 South Michigan Avenue

Opened around 1926 , this branch of a popular New York restaurant started in 1850 by Henri Maillard, a French caterer who was in charge of Lincoln ’s inaugural banquet, was perhaps the largest restaurant in Chicago Straus Building

It was very well furnished and elegantly decorated and the food was very well prepared. Many high society women loved the Afternoon Tea on the top floor of the building tower that was open in the summer time and where the view of Chicago

Other Restaurants that either served French food or had French chefs:

NEW COLLEGE INN in the Sherman Hotel at Randolph and Clark

The head chef in this famous hotel owned by the Byfield Brothers, was a Monsieur Jean Gazebat, who had worked at Chez Prunier and at Café de Paris, in Paris

He was one of the most renowned seafood chefs in Chicago and his specialty was a Bouillabaisse à la Marseillaise, that Drury says was as good as the one you could eat at the original Prunier in Paris

CAFÉ FRANCAIS 1922 Calumet Avenue

Drury says that this elegant mansion transplanted from the Gold Coast, that catered to a clietele of publishers, offered an excellent French cuisne with the best filet mignon in town.

CHEZ DORE 212 East Erie

It had a very good French chef and catered to employees of businesses, art studios, and office buildings of that neighborhood .

The cost of luncheon and dinner was $ 1.50

This was perhaps the only Theatre-Restaurant in the United States North Shore loved to dance after a good French dinner made of very elaborate and special dishes created by French chef Pierre, a veteran of the Tour D’Argent in Paris

In the Casino and Main dining room you could dine while watching a show or listening to musicians from Havana , Cuba

The owner of this Monte-Carlo like ‘’pleasure palace’’, as Drury describes it, was also a Frenchman, Albert Bouche who also owned a similar Villa Venice in Miami Beach

The bills were quite high for the time: from $ 3.50 to $5.50 for Table d’hôte dinner + $ 3.00 cover charge on week-ends.

This place, that had the reputation of attracting both patrons and entertainers who might have had mob connections, burned and was re-opened many years later in the sixties.

Flashback 2 : From 1939 to 1959

Not much happened in terms of creations of authentic French restaurants in Chicago

Even though a record number of restaurants were created between 1939 and 1945, the war and its restrictions, the amplification of the ‘’cooking at home’’ movement or eating out in casual restaurants did not stimulate the arrival of new French chefs in our town.

Besides, other immigrants like the Chinese, Eastern-Europeans, Russians, and Germans, as well as Greeks and Italians started modest Mom and Pop ethnic family-oriented eateries that better corresponded to the needs and palates of that era.

There was also an exodus to the suburbs of young families who were not naturally inclined to go out and eat French food .

And generally speaking this period was marked by a strong return, as it had been the case in the early 20’s after WW I, to a sort of ‘’eat American’’ tradition, partially facilitated by the expansion of frozen foods, fast food, TV dinners, etc.

The Korean war reinforced this return to American values and a certain isolationism in eating habits that did not stimulate the popularity of fancy French food or restaurants.

The restaurants that really attracted a lot of new customers where fancy places patronized by celebrities like the new Pump Room in 1938, and restaurants, or supper-clubs with entertainment, like Chez Paree, or ballrooms in large downtown hotels.

Several of these places offered steaks and lobster as well as exotic cocktails rather than Coq au Vin and Bordeaux

One of the rare exceptions was the launching in 1941 of Café De Paris in the Park Dearborn Hotel at 1260 N. Dearborn Parkway, where famous French chef Henri Charpentier created his signature dish ‘’Duckling Belasco’’ flavored with a Grand Marnier or Cointreau sauce. For years Charpentier claimed to have invented by chance the ‘’crèpe Suzette’’ when he was working at another much more celebrated Café de Paris in Monte-Carlo, as an apprentice waiter in the late 1880’s.

Charpentier had solid references. He worked for celebrities such as Escoffier and Cesar Ritz.

The restaurant was acquired by Edison Dick and Ray Castro in June 1952.

That same team (Dick-Castro) also started in 1959 Maison Lafite, in the Churchill Hotel at 1255 North State, a very French provincial looking restaurant that remained successful until the early seventies.

Its menu looked very traditional French (Coq au vin, Veal scallopini, Dover sole, Chateaubriand Bearnaise, etc). But my impression is that it was, like many of the Castro restaurants, probably more French in appearance and style than in authenticity of its cuisine.

Its menu looked very traditional French (Coq au vin, Veal scallopini, Dover sole, Chateaubriand Bearnaise, etc). But my impression is that it was, like many of the Castro restaurants, probably more French in appearance and style than in authenticity of its cuisine.

One interesting case: John Snowden, who would become better known in the late 60's and early 70's with his cooking school and catering services, Dumas Père, opened a French Restaurant, Le Provencal, in Hyde Park in 1951. He had a very solid knowledge of classic French cooking that he acquired during a 6 year stay in France and 3 years of studying at the Ecole d'Hotellerie of Lausanne in Switzerland. But, in spite of the backing of some investors linked to the University of Chicago, Le Provencal failed, in part due to the difficulty to find adequately trained staff , and probably a lack of a local client base, in that part of town.

In a Tribune article published in 1979, the very good Chicago chef John Terczak (Biggs, Gordon,) who studied under John Snowden, said that in spite of the fact that he was a very demanding teacher, Snowden was "probably the best chef in the city".

In a Tribune article published in 1979, the very good Chicago chef John Terczak (Biggs, Gordon,) who studied under John Snowden, said that in spite of the fact that he was a very demanding teacher, Snowden was "probably the best chef in the city".

In 1964 he would try again with his Cafe La Cloche in Old Town.

I believe that L’Aiglon, Jacques French Restaurant and Le Café de Paris are the only 3 major French restaurants that survived that difficult period.

Most photos are coming from John Chuckman's marvelous collection of vintage postcards that can be found on his website Chuckmanchicagonostalgia.worldpress.com

Next Episode: 1960-1969